Semantic search is a bit like LiDAR: it penetrates the data's lexical canopy to reveal underlying meaning. In “Part 1: Fundamental Power” and 'Part 2: Key Details' we covered the basics of FileMaker semantic search. Now let's consider some more exotic ways this new feature can put a spotlight on our data.

We'll show an example of 'unified search' across multiple tables, using natural language to construct a semantic search. Then we'll extend this to a second example, showing 'unified search + actions'. A downloadable demo/tutorial file is provided for each of these two examples.

Unified Search

If you’ve ever built a unified search into FileMaker (like in my Things example from years ago), you already know the power of allowing the user to search across multiple tables simultaneously, without first having to think about which table might house the data they’re looking for. (Perform Quick Find does something similar, but at the field level.)

With embeddings in FileMaker 2024, unified search just got more powerful. In this demo, all the embeddings for the various data tables are stored in a shared Embedding table. The semantic search, via Perform Semantic Find, is then performed on that Embedding table.

Unified Search example

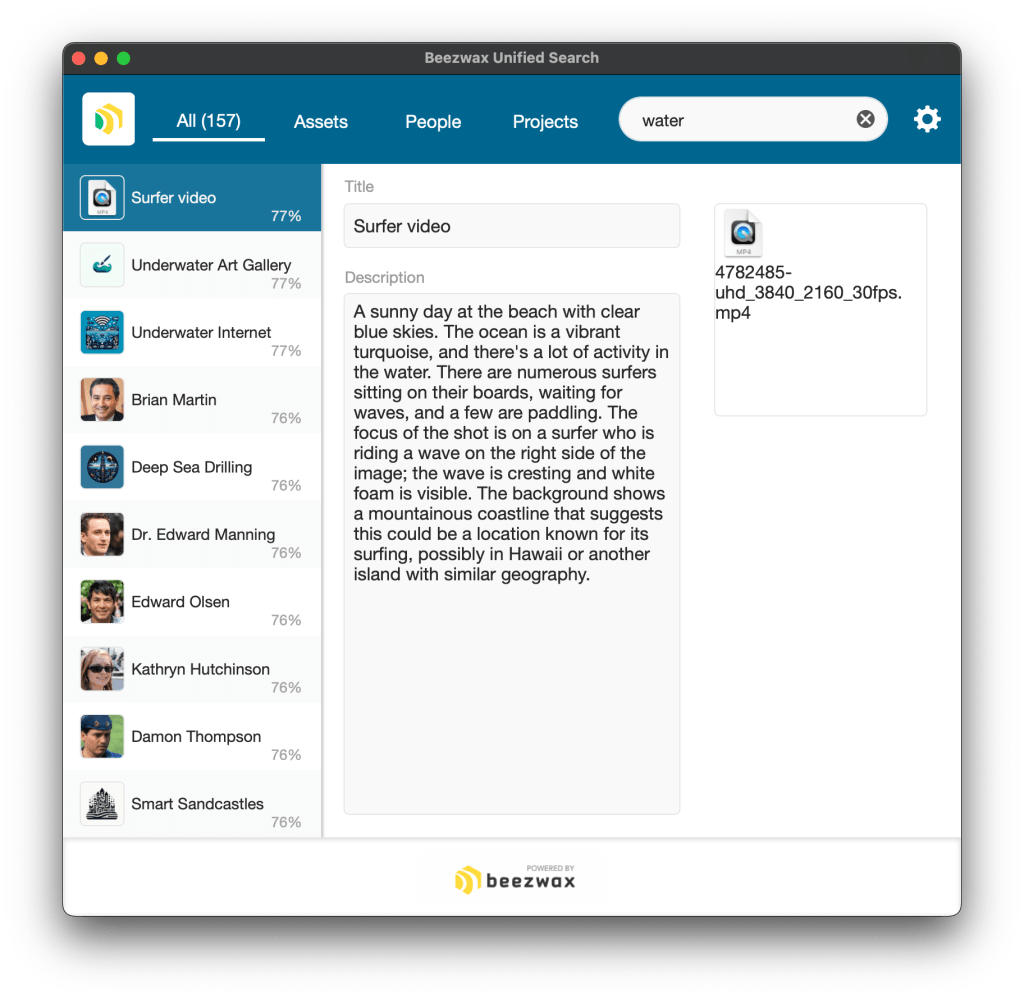

I built a demo solution, which I'll also share as a download below. This app manages data for three main entities: Assets, People, Projects. It's built to enable unified search, and use FileMaker semantic search.

When I search for 'water', the first 10 results include:

- 1 asset (a video described as being about surfing)

- 4 projects (with clear connections to water)

- 5 people (with hobbies like aquascaping and scuba diving).

The user is able to search all tables simultaneously, using natural language, and see the most relevant results at the top of their resulting found set. They are freed from trying to anticipate how the data is structured in the schema, and are unhindered by how the text was syntactically structured when input in the records.

So cool. I can’t wait to consider this for all of my apps. Now let's work through some deployment considerations, and

Storage

I haven't yet mentioned storage. Embeddings take up space. The size of an embedding is determined by how many dimensions your chosen embedding model uses, not by the size of the text you are embedding. So you should expect a consistent storage footprint across all embeddings. (With 1,536 dimensions, I'm seeing ~179kb per embedding.)

It's a best practice to store your embeddings in containers, because they will be more performant and will require less storage. You can employ external storage on those containers to keep your app’s storage size slim (but you should read the section on 'Performance' below).

Here's where unified search comes into play. If you store all your embeddings in a single table, you only have to configure your external storage in one place, rather than once per data table. Likewise you only have to add a calculated cosine similarity field in one place.

Flexibility

Maybe unified search sounds good for some scenarios, but not all. In the example file, take a look at the search when performed from the context of the People or Projects screens. Those semantic searches leverage the shared Embedding table, but the user's context limits the results to records from a single data table.

You could even script a manual find on the Embedding table first to limit the found set to records from a specific table (e.g., all active projects), and then use Perform Semantic Find's 'Record set: Current found set' configuration to search only within that established subset of records.

Performance

I've mentioned that storing the embedding as a container is more performant than storing it as text. What about other performance implications?

First, storing the container embeddings externally will perform slower than storing those containers in the file. But remember, regardless of storage method, container data is not included with a record when a user downloads that record. That's important because adding embeddings to many tables will bloat storage, but we don't want users to pay the performance cost to download that bloat every time they want to view an embedded record. FileMaker's container storage saves us from this: container data is downloaded only as needed (e.g., when needed for a semantic search).

Second, and more generally, performant semantic search relies on solid hardware. Testing this on a quad-core Intel MacBook Pro, things felt snappy at first (with only hundreds or a few thousand records). Things started to slow down beyond 50,000 records, though, and became especially slow after 100,000 records (note that it matters how many records are searched, not how many records are in the searched table).

| Records Searched | First Search | Subsequent Searches |

| 50,000 | 22 seconds | 3 seconds |

| 75,000 | 35 seconds | 5 seconds |

| 100,000 | 124 seconds | 31-36 seconds |

Uh oh; those numbers aren't looking good. And they aren't even hindered by latency. So what are the numbers when hosted on FileMaker Server?

| Records Searched | First Search | Subsequent Searches |

| 50,000 | 3 seconds | 3 seconds |

| 75,000 | 12 seconds | 3 seconds |

| 100,000 | 16 seconds | 3 seconds |

So the hosted file, on a machine with better hardware, is more performant at 100,000 records than is a local file on my lesser machine at only 50,000 records. That's reassuring.

Those metrics are for searching directly on the embedding table. What about the scenario I propose above where I supplement direct searches with searching through a relationship (e.g., my layout is based on the Project table, but each project's embedding is stored in a related Embedding table)? It's not good. Even at 5,000 records (on the hosted machine described above), it took 220 seconds! At 100,000 records I terminated the process after waiting an hour.

In the project example, I could solve the performance issue by first finding all project-related embedding records; then performing my semantic search as a constraint on those records; then, if necessary, using Go to Related Records to arrive back at a layout based on the project table. That sounds cumbersome already, and there's another complication: when I arrive at those project records I will have lost semantic search's sort order; so I'd need to recreate that as well.

To circle back, a unified search brings together into a single table representations of records from various tables. And so the unified search table would necessarily grow to be the superset of record counts from those participating tables.

High record count = slower performance.

Therefore for unified search in particular, but semantic search in general, we want the best hardware possible, and we need to be smart about limiting the records to be searched when we can.

Tutorial / Demo File

Download Beezwax Unified Search.fmp12 (26.9 MB)

- Download includes a FileMaker (.fmp12) demo file, LICENSE and README.

- FileMaker 2024 (v21.x) is required to use this demo file.

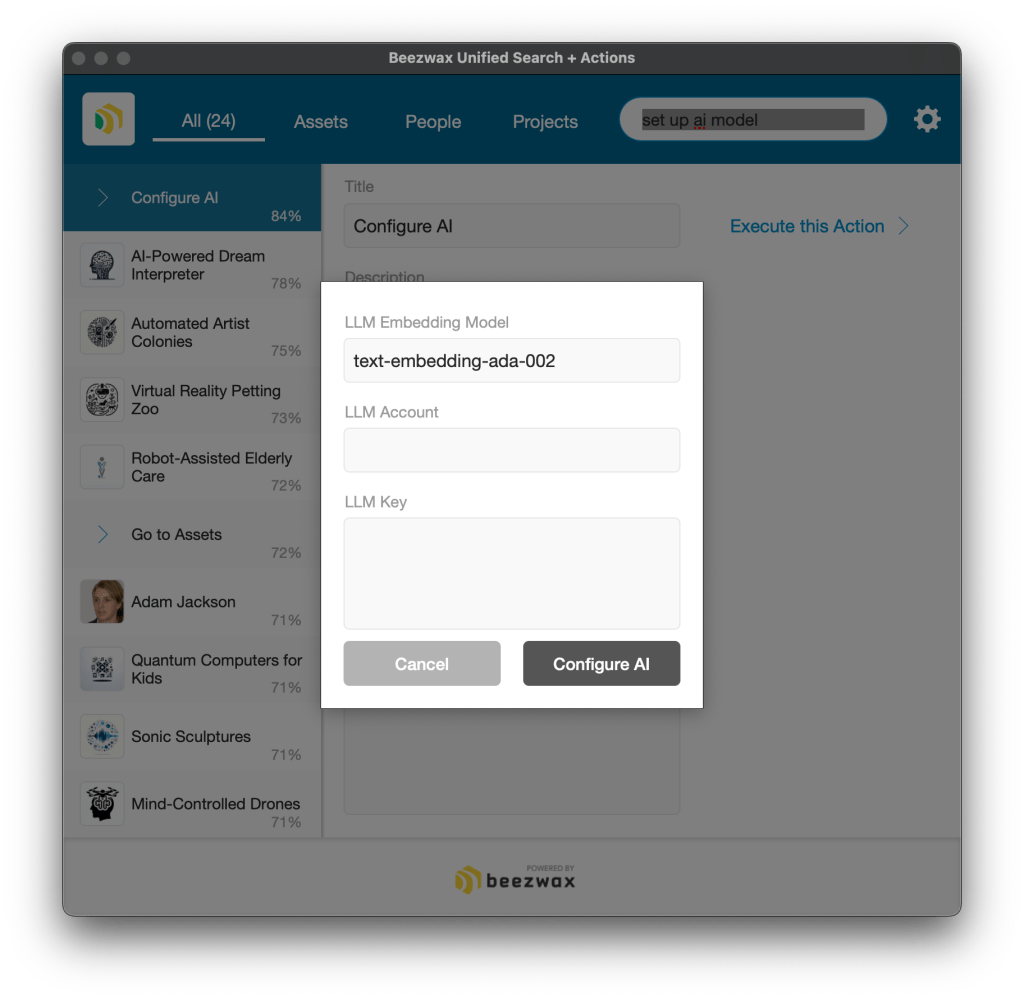

- For both demo files in Part 3, and those in Part 1 and Part 2, you'll need to supply your own AI credentials to use the file (via the gear icon in the top right).

- If you employ credentials that aren't from OpenAI, you'll also need to configure the LLM Embedding Model field and execute the embeddings script (to build embeddings compatible with the embedding model you've chosen).

But, wait, there's more!...

Unified Search + Actions

In this next demo, I extend the Unified Search demo to include a table of actions. The spirit of the unified search is that the user shouldn't need to think about how the data is structured. Adding actions takes that a step farther: the user shouldn't have to distinguish between finding something and doing something. With a unified semantic search, we can offer the user a complex collection of options relevant to their search term.

If I search for 'set up ai model', my first result is the 'Configure AI' action.

When I click the 'Execute this Action' button, it opens the AI configuration window.

To reiterate the power of this approach: the user didn't have to specify whether they were trying to find something or to do something. For any search term, a user might be searching for data records, or they might be searching for documentation on how to perform an action, or they might be trying to access the action itself. With a semantic search (and some UX design love) the app can surface a complex mixture of results to the user and let the user decide which result best satisfies their need.

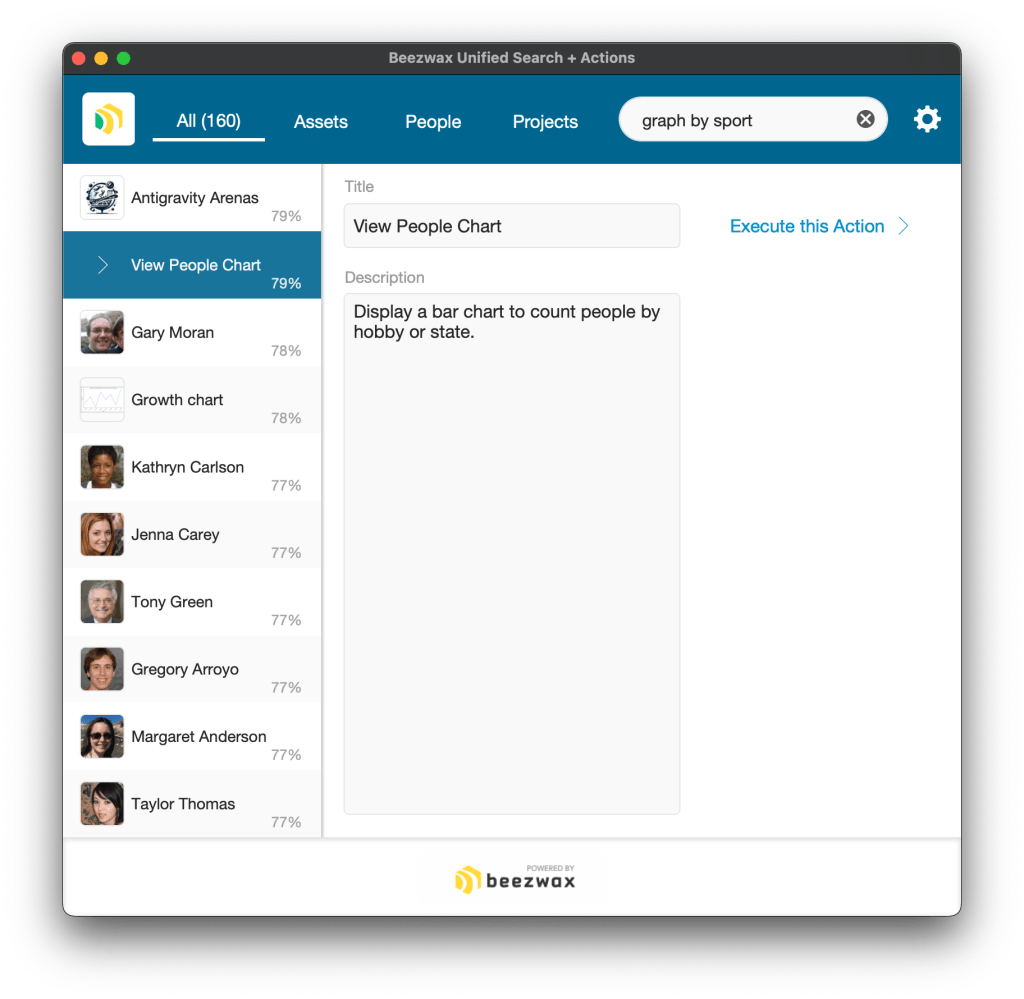

The above example action is simply executing a navigation script. But what if we want something a bit more complex? Next I search for 'chart by state'. The first result is the 'View People Chart' action, because of its semantic similarity to 'Chart' in the action name, and because it understands that 'People' relate to the 'state' field.

Executing that action produces this chart, a count of people by state.

So what's going on here? The semantic search surfaced the 'View People Chart' action, but from there I hardcoded the action itself:

- Go to the People layout.

- Show all records.

- Sort by the State field.

- Build up a count of people by state.

- Open a card window to display a chart with the summarized data.

Generating a chart from a search term is cool, but not if it always assumes I want to summarize by state (and I wouldn't want to create an action record for every permutation of chart I might want to support). So next I search for 'graph by sport'. The semantic search surfaces that same 'View People Chart' action (note that this time I searched for 'graph' instead of 'chart').

If I execute that action (the same action I executed in my previous 'chart by state' example), I get this chart, a count of each person within each sport-related hobby.

Okay, now this is getting interesting. So how does it do that? The app used a semantic search to surface the 'View People Chart' action. Then, when the user clicked the 'Execute this Action' button, the app leveraged the semantic meaning of the search term two more times:

- The script calculated the cosine similarity between the search term 'graph by sport' and the word 'hobby', and found a significant similarity. So from there it branched into a hobby-centric summary (instead of a state-centric summary).

- The script performed a semantic search on a table of hobby records, looking for those hobbies with a high cosign similarity with the search term, more or less finding hobbies that are related to a 'sport'.

That means the search term 'graph by sport' was leveraged for three distinct semantic comparisons:

- To find the 'Chart by Person' action record.

- To determine that the chart should be based on the Hobby field.

- To identify the specific hobbies to include in the chart.

I said earlier that a user might want to find something...or...they might want to do something. But notice how the search term 'graph by sport' supported both: it allowed the user to generate a chart of hobbies (doing something), but only inclusive of a specific subset of people, those with sports hobbies (finding something). How cool that the user can input their need in their own way, and the burden is offloaded to the app to parse out the which part of the search term relates to the action the user wants to perform, vs. to the data the user wants to find.

Reiterating a point I made in Part 2, this shouldn't be the only way to get to a chart like this. Users still need unambiguous ways to access your app's actions.

Tutorial / Demo File

Download Beezwax Unified Search + Actions.fmp12 (28.2 MB)

- Download includes FileMaker (.fmp12) demo file, LICENSE and README.

- FileMaker 2024 (v21.x) is required to use this demo file.

- For both demo files in Part 3, and those in Part 1 and Part 2, you'll need to supply your own AI credentials to use the file (via the gear icon in the top right).

- If you employ credentials that aren't from OpenAI, you'll also need to configure the LLM Embedding Model field and execute the embeddings script (to build embeddings compatible with the embedding model you've chosen).

Control Group vs. Test Group

Beneath the fancy scripting and layouts, our FileMaker apps have a database as their skeleton. The database's job is to structure the data, and it can do so without having to understand that data. In particular, when we're talking about fields that contain large text strings, the burden of understanding the data is traditionally placed on the users.

Throughout this blog series I've stressed that semantic search frees the user from having to know/recall how data is phrased, because we're searching the meaning of strings, not the literal words or characters in those strings. To put this another way, semantic search allows a user to leverage a string they understand (their own search term) to find a string they don't necessarily understand (in the sense that the user might not know how the text was phrased).

However, if you recall the Resumes example from Part 1: the user's search term was a string they weren't familiar with (a candidate's resume), and the found records were strings the user probably was familiar with (tightly crafted job postings). So, whereas typically we might use semantic search to find records, let's explore how semantic search can help us understand the meaning of the search term itself. (And for this example, we should think of it less as a 'search term' and more as an 'input'.)

Imagine our client works in the climate technology sector. The client wants to review a set of academic papers relevant to their field, even if the paper wasn't tagged in a relevant way, and even if the paper was published in some other field. We can't expect the client to read all papers on all subjects, so how can a FileMaker app help?

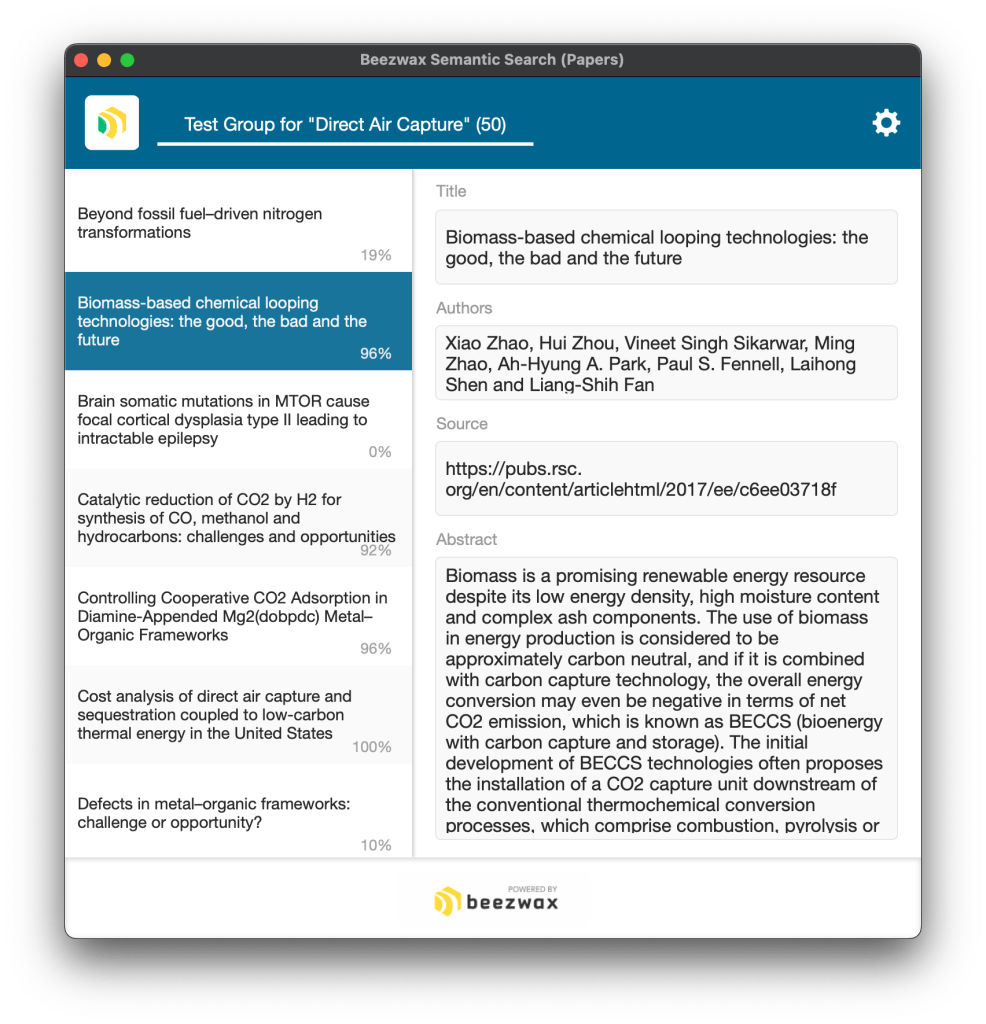

First, the client identifies in their FileMaker app a subset of papers already known to be relevant to each area of focus. For this example, the client tags 100 papers with 'direct air capture'. We'll call this our control group.

Second, we want to validate that our control group consists of papers with a similar subject matter. We build an embedding on the title+abstract of each paper in the control group, then we compare them all to each other to score them. For any one paper, we derive its score by performing a semantic search to find papers with the 'direct air capture' tag that have a ≥ .8 cosine similarity with the paper in question. We expect it to always find itself, and up to 99 others, giving us a score in the range 1...100, where 100 means the paper is at least 80% similar to all 100 of the 'direct air capture' papers.

Here I've sorted the control group with the lowest score (95%) at the top. Most papers score 100%. So that reaffirms that indeed the control group consists of closely related papers. I've highlighted a record that doesn't include 'direct air capture' in its title, yet still scores higher than 5 papers in the control group that do include that string in their titles.

Third, we want to add a test group. These are papers the client hasn't read, and so it is unknown whether they relate to 'direct air capture'. We plug in 50 papers, and ask for that same semantic comparison to the control group (papers in the test group will be scored in the range 0...100, since it's possible to relate to no papers in the control group).

At left we see the 50 papers in the test group, along with their score. 'Beyond fossil fuel-driven nitrogen transformations' scores only a 19% (meaning it is 80% similar to only 19 of the 100 papers in the control group), so that's a dud. But 'Biomass-based chemical looping technologies: the good, the bad, and the future' scores 96%! That's a winner, and worthy of human review.

So imagine an automated process that mines the digital repositories where these papers are published, uses a semantic search to score a new paper's relevancy to a topic of interest, and surfaces to our client those papers with the highest score. In effect our app would be skimming a large volume of material, and only bothering our client to review the most relevant papers. Think of the hours saved when our client can focus their time on just the most promising papers.

The app wouldn't need to stop there. Using semantic search, we could layer subtopics, e.g., 'adsorbent materials'. And using existing Insert from URL AI integration we could add sentiment analysis ('how is the paper portraying direct air capture'), topic area analysis, and other deeper analyses of the papers. Whether for academic papers, or research papers papers in general, or even more broadly any kind of analysis where we need to understand how a new piece of information fits into our data, semantic search is ready to help.

To clarify, this technique isn't the same as training a model. The app doesn't actually understand anything about 'direct air capture', and it's unprepared to answer other questions about the data. Yet for our purposes, it's able to 'read' a paper's abstract and decide whether it meets our criteria of relevancy.

Credit to my friend John Cornwell for bringing this scenario to my attention, and for providing links to all the papers.

For a visualization of this idea, check out Michael Wallace's 3D model of a semantic search, especially at the 10:59 mark. The model allows us to see the geographic relationship between a test record and the control group. Very cool.

Summary

If you're excited to add FileMaker semantic search to your solutions, but are unsure of the effort, I have good news. In its simplest implementation, including creating embeddings for 500 records, it can take just 5 minutes. That's so fast. It's like I'm sprinkling fairy dust on my app's search to make it fly. It's so easy it almost feels like cheating.

Semantic search augments an app's core function: retrieving data. Now a user can ask for the data they want, in their own words, and our apps will be able to (better) understand what the user is looking for. Data dies in the dark, so let semantic search turn on the lights.

FileMaker 2024 Semantic Search - Reference Blog Posts

Stained glass art © 2024 Uma Kendra, used with permission.